THE SNOW STAR FADES

(La estrella de nieve se desvanece)

“The pilgrimage to the Lord of Qoyllur Rit’i, an annual religious celebration, has been an integral part of Andean tradition and beliefs. But climate change and COVID-19 are threatening that.”

Text by Amanda Magnani

Photographs by Armando Vega

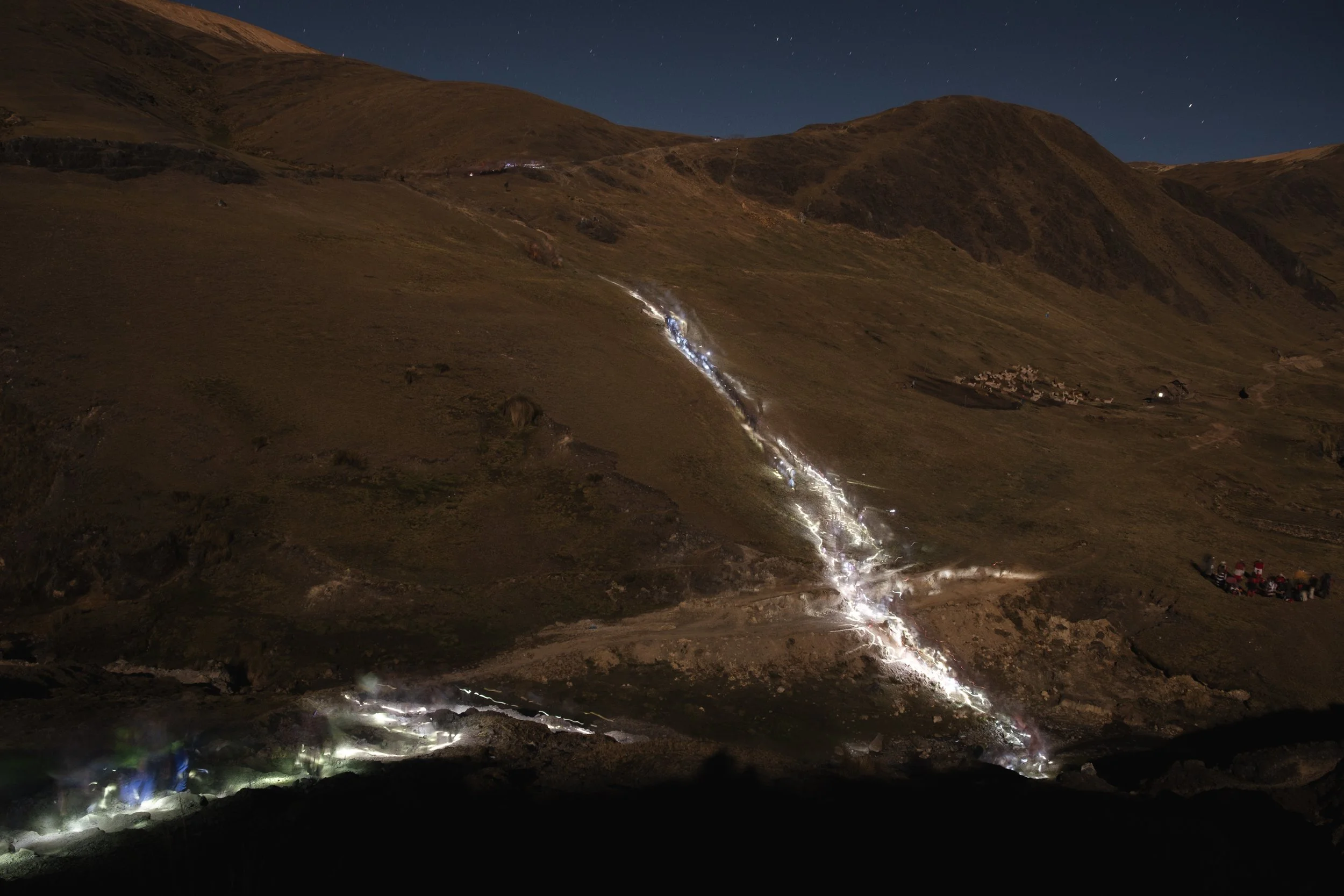

At night, believers would use the reflection from the moon that cascaded atop snow-capped peaks as a guide to make their way up the sacred Colque Punku glacier. The tradition goes back centuries for pilgrims from various indigenous groups in the Andes who have made the journey through the Sinakara Valley in Peru during four days of religious festivities known as Qoyllur Rit’i, Quechuan for “the snow star.”

“When you go to Qoyllur Rit’i, you’re in a different space,” says Richart Aybar Quispe Soto, who has taken part in the pilgrimage for more than 35 years. “You get there, and you’re transformed. I go there to be in the snow, to be near the stars, to be close to the moon. I go there to see the first ray of the sun at dawn, to wait with great devotion, to return purified. Up there, we are reborn.”

But in recent years, the Colque Punku has lost some of its brilliance. The snow that turns into ice that forms the glacier is melting. Researchers have determined that tropical glaciers in the Peruvian Andes have decreased in size by about 50 percent in recent years.

“The effects of climate change today are not only compromising our survival but our ability to find meaning,” says photographer Armando Vega, who has been documenting the Qoyllur Rit’i tradition since 2017. “I hope the pilgrims' display of reverence to an element of Mother Earth can change people's perception of nature not only as a resource to be exploited for our communal gains, but as a gift that must be preserved, as a window to the human spirit.”

The Snow Star Festival has been an integral part of Andean tradition and beliefs. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, some 100,000 pilgrims would make their way to the Ocongate district in the southern highlands Cusco region of Peru.

Traditionally in late May or early June, the festival mixes Roman Catholic and indigenous beliefs, honouring both Jesus Christ as well as the area’s glacier, which is considered sacred among some indigenous people. A central part of the pilgrimage is a sanctuary at the base of the mountain where a boulder features an image of Jesus Christ known as the Lord of Qoyllur Rit’i (pronounced KOL-yer REE-chee). Believers dance and pray long into the night, seeking health, peace and prosperity.

But the pandemic changed everything.

Prior to COVID-19, there had been no record of the pilgrimage ever being canceled. Yet, 2020 and 2021 didn’t see the festival taking place. Peru faced the world's highest COVID death rate. As of August 2022, the country of 33 million people had registered 215 thousand deaths caused by the coronavirus – a per capita death rate unequaled elsewhere.

“This situation is surprising, because nothing like this has ever happened before. It was not something any of us could have anticipated”, says Willington Callañaupa Quispe, chairman of the Council of Nations of the Brotherhood of the Lord of Qoyllur Rit’i since 2021. “But we have to be realistic about it. We all felt the effects of the pandemic in our own flesh. We have lost many dancers and pilgrims to COVID-19.”

The festival took place again this year for the first time since 2019, but with an entire new face. To avoid the customary crowds of tens of thousands of pilgrims, each nation of traditional dancers was assigned a separate date to peregrinate to the sanctuary and pay their respects to the Lord of Qoyllur Rit’i.

“It was heartbreaking”, says photographer Armando Vega. “Rather than a festival, it felt like being in a mourning procession. People looked sad, crestfallen.”

It might as well have been a funeral. As the pilgrims reached the mountains again, the remains of the sacred glaciers they encountered had receded to such a distance that it was only possible to reach them with the support of an expert mountain guide.

“We are not losing the ground we walk on. We are losing our mother,” Hélio Regalado, who has participated in the pilgrimage for 10 years as a Wayri Chunchu dancer, says of the melting glacier.

Aybar Quispe, another one of the indigenous dancers known as the guardians of the glacier, says he is saddened by the knowledge that the melting ice means future generations will not experience the same kind of cleansing from the snow he was blessed with growing up.

“If the glacier were to disappear, I wouldn’t lose my faith if I couldn’t go to Qoyllur Rit’i, but I would be heartbroken,” he says. “A part of me would disappear.”

The Andes, the longest mountain range in the world, spans seven countries — Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile, Argentina and Peru. Seventy percent of the world’s tropical glaciers are in Peru and various studies have raised alarms at the rapid rate of melting ice in the region. For almost two decades, that has been changing some of the longtime rituals.

Already in 2004, in an effort to slow down the rate of the melting glacier, festival organizers banned the practice of cutting blocks of ice to share with the community, believing the melted water had healing powers. “Many have cried. They broke down in tears, for this was a tradition of hundreds of years—but we had to make the decision to stop,” says Norberto Vega Cutipa, previous chairman of the Council of Nations of the Brotherhood of the Lord of Qoyllur Rit’i.

Pilgrims remember the thick layers of ice from years past when the glacier was just a short distance from the site of the sanctuary and the moon illuminated the way.

“When I walked up years ago, we didn't need, as we do today, lanterns to find the way,” says Quispe. “We had enough light from the glacier. When we arrived there at night, the moon began to rise—the mother moon—and little by little the area looked as if it were daytime. It was like heaven; it was a dream.”

“Describing how the glacier used to be is like trying to explain colors to a blind man,” says Quispe’s son, José Isaac Quispe Peralta,” also a dancer. “It’s impossible.”